'An unapologetic pulse of defiance': a guide to the works of the incomparable Jamaica Kincaid

Jamaica Kincaid's books are beloved for their candour, insight and honest exploration of familial relationships and colonial legacy. Here, Leah Cowan shares her guide to just some of Jamaica Kincaid's must-read works.

Whether ascending a Himalayan foothill in spite of a raging hangover, or recounting a young au pair’s detachment from her mother back home, the writings of Jamaica Kincaid thrum with an unapologetic pulse of defiance. Her work is often lazily described as ‘angry’; an adjective hastily assigned to black women who dabble in speaking their minds. More accurately, Kincaid’s books are impassioned and darkly humourous; her succinct ruminations on the violence of colonisation and structural racism are deft and razor-sharp.

Jamaica Kincaid was born and raised in 1950s Antigua. Under the instruction of her mother, she moved to New York as a teenager to become an au pair. Kincaid studied photography and went on to win a scholarship, but returned to New York where she became a staff writer for The New Yorker. Her writings are potent; heavily weighted with analysis of power and its abuses. Award-winning author of How to Love a Jamaican, Alexia Arthurs, describes Kincaid’s novels as “a lesson in Caribbean feminism – that navigation of doing and being and desiring without permission and in spite of hypermasculinity and misogyny”; as in Arthur’s short stories, men figure in Kincaid’s work as both disposable objects and looming threats.

Kincaid’s keen eye both for details of external setting and characters’ interior worlds means that even in her slimmer volumes, her protagonists are consistently believable and relatable. Kincaid’s thematic choices are rich and turbulent: relationships between mothers and daughters, employers and workers, and colonisers and the colonised are fertile ground for literary exploration. Fertile ground itself is a common thread. Kincaid’s joyful obsession with plants, gardening and the natural world invites us to decolonise our gaze; to place value not in what is definable and governable, but to indulge in the pleasure of nurturing and stewarding those things – be it friends, lovers, or window-box perennials – that we ultimately can never control.

A guide to Jamaica Kincaid's books

At the Bottom of the River

by Jamaica Kincaid

At the Bottom of the River (1983) is a phenomenal collection of poetic vignettes and experimental musings on the fabric of life and afterlife. The collection opens with a pounding sermon on how a girl must behave, shot through with the author’s own dry observations on the imperative to avoid ‘becoming a slut’, and, relatedly, to abandon all pre-colonial forms of music and expression, such as ‘singing benna’ (a style of calypso music which originated in Antigua). The book dreams backwards and forwards, adopting the form of memoir when considering the different directions her life could take, including “marrying a woman [...] who wears skirts that are so big I can easily bury my head in them”. Throughout, undulations of mother-child relationships are present, and in some senses these bonds are toxic, and fatal. The arc of the narrative examines aspiration and disappointment; the book is a brief but well-drawn journey into the human condition.

Annie John

by Jamaica Kincaid

Often understood as a follow-up or ‘decoder’ to At the Bottom of the River, Annie John (1985) is ostensibly Kincaid’s debut novel, which centres around a debated queer romantic arc. The book expands on the amorphous ideas which are more impressionistically laid out in her previous publication. It follows the loose structure of a ‘bildungsroman’ or coming-of-age narrative, while also subverting colonial ideas of power and control, most notably through the decentring of hetrosexuality. In the novel, the protagonist Annie John develops romantic feelings for her friend Gwen. The girls’ queer explorations have been described by Kincaid as 'just practicing' for their straight futures. Alternatively, queer readings of the text see resonance in the protagonist’s separation from her restrictive mother and motherland, in pursuit of a more liberated options elsewhere.

Lucy

by Jamaica Kincaid

Lucy (1990) is Kincaid’s ‘künstlerroman’; an autofictional narrative which explores an artist’s growth to maturity. The book closely mirrors the author’s own life, opening with the protagonist’s first day working as an au pair after being sent away by her mother. Towards the end of the book, the protagonist offers a neat summary of this journey: “one day I was a child and then I was not”. Of course, the reality holds far more complexity; Lucy chronicles the struggle of being immersed in the unfamiliar while processing the trauma of abandonment. Lucy’s astute and pithy observations about her employer are amusing, and hold generous compassion. Throughout, the protagonist - a black, working class woman - defiantly returns the gaze of those who through their wielding of soft and overt power seek to control her.

The Autobiography of my Mother

by Jamaica Kincaid

Where Kincaid’s earlier works focus on child and adolescent perspectives, The Autobiography of my Mother shifts to the other end of the life spectrum, telling its story through the lens of a woman in the seventh decade of her life. The novel’s protagonist is Xuela Claudette Richardson, whose mother passes away during her birth. The Autobiography of my Mother explores themes of oppressive social structures such as racism and misogyny with Kincaid’s ever-present pragmatism; at one point Xuela notes 'To want desperately to marry men, I have come to see, is not a mistake women make; it is only that, well, what is left for them to do?'. The Autobiography of my Mother is a striking denouncement of imperial violence, and Xuela’s narrative stands firm in rejecting external demands, by defying colonial and patriarchal acts of silencing, and sharing her story through the page.

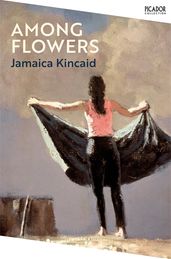

Among Flowers

by Jamaica Kincaid

Among Flowers provides a fascinating, if at times naïve meditation on the sublime unknowability of nature. Documenting a three-week trek through Nepal, the author invites the reader to find joy in reckoning with our own smallness in the face of intimidating geography. Perhaps Kincaid’s most informal text, the author presents herself as an imperfect traveller, prone to objectifying her companions; at one point a porter is referred to simply as ‘table’; the object he lugs up the Himalayas in service of Kincaid and her companions. Elsewhere, Among Flowers demonstrates Kincaid’s reflectivity: she critiques ways of looking at and relating to unfamiliar places. Reminiscent of other writers who demonstrate critical self-awareness when they enter a new landscape (Susan Sontag and Johny Pitts spring to mind), Kincaid is first to poke fun at her own failings. The author’s effervescent joy when collecting seeds (the purpose of the trip) is a pleasure to read.